Over the past two decades, doctors and researchers have observed a troubling shift: colorectal cancer is showing up more frequently in younger adults. Once considered a disease mostly affecting people over 60, colorectal cancer is now being diagnosed in individuals as young as their 30s—and sometimes even earlier. Today, roughly 1 in 5 new colorectal cancer cases occurs in someone under 54. What makes this especially puzzling is that overall rates of the disease are going down in older populations, thanks to better screening and awareness.

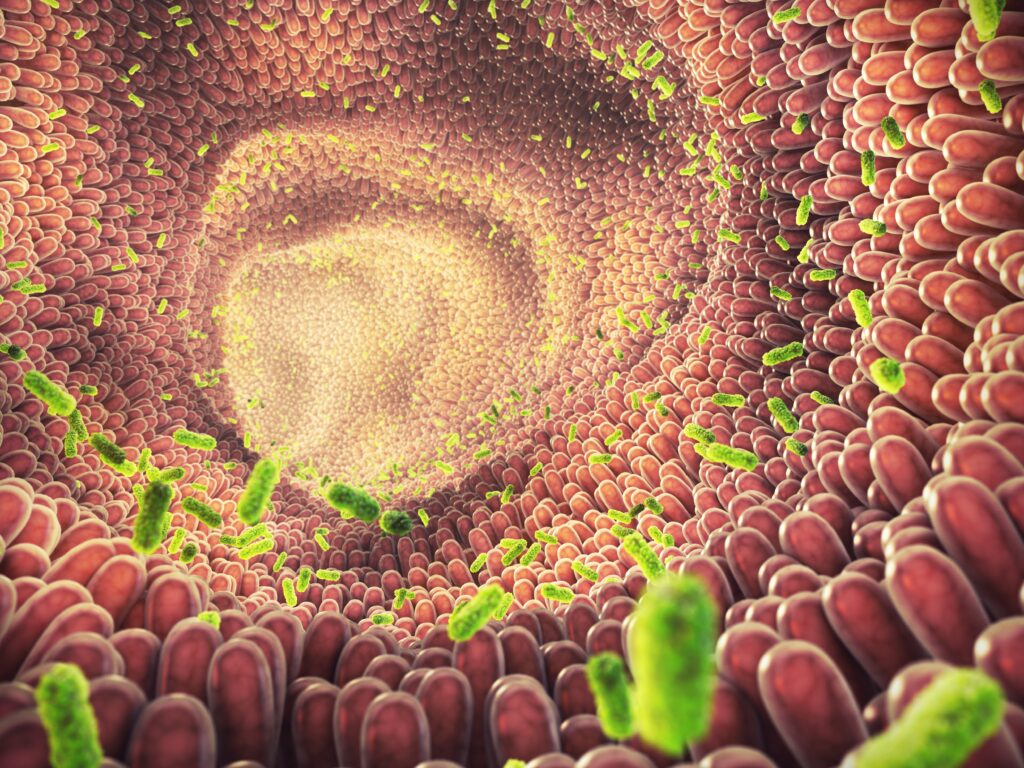

This surge in early-onset cases has raised urgent questions. Why are more young adults getting a type of cancer traditionally linked to aging? Could environmental or lifestyle factors during childhood play a role? A large international study published in Nature offers one of the clearest leads so far: exposure to a DNA-damaging toxin called colibactin, produced by certain gut bacteria, may be quietly seeding cancer risk in early life—long before symptoms ever appear.

The Rise in Colorectal Cancer Among Younger Adults

Colorectal cancer used to be considered a disease of aging, with screening guidelines historically focused on those over 50. That framing no longer fits. Over the past two decades, cases among adults under 50 have surged—rising by more than 100% in some regions. In the U.S., for example, people in their 30s and 40s now account for about 1 in 5 new colorectal cancer diagnoses. What’s especially concerning is that this trend is happening in the absence of widespread screening in these age groups, which means many cases are caught at more advanced stages.

Unlike older adults, younger patients with colorectal cancer often present with tumors located in the distal colon or rectum, and they may not have any known genetic predisposition. In fact, most early-onset cases are considered sporadic, arising without family history or inherited conditions like Lynch syndrome. This disconnect from traditional risk factors has challenged long-held assumptions and forced researchers to consider new explanations.

Environmental exposures, diet, early-life antibiotic use, sedentary behavior, and shifts in the gut microbiome have all been proposed as contributing factors—but pinning down the biological “how” has remained elusive. Large-scale genome sequencing studies now offer a new approach: by analyzing the DNA of tumors themselves, scientists are uncovering molecular patterns—mutational signatures—that act as historical records of what the cells have been exposed to. These patterns are now helping to connect the dots between early-life events and cancer risk decades later.

What’s emerging is a picture where geography, age, and molecular biology intersect. Colorectal cancer doesn’t just look different in younger patients—it behaves differently at the genetic level. And the clues embedded in their DNA are starting to tell a story that challenges the idea that this is simply bad luck or genetics alone.

Why Childhood May Be the Window of Risk

The idea that cancer risk could be shaped in early childhood isn’t new—but this study offers molecular evidence to support that theory in colorectal cancer. Researchers found that the DNA-damaging signatures caused by colibactin were not just present in tumor samples—they were imprinted early, during the first stages of cancer development. These were not recent mutations. They were early clonal mutations, meaning they occurred before the tumor had fully taken shape, and remained detectable years or even decades later.

This has important implications. If colibactin exposure is happening early in life, then factors that influence a child’s gut microbiome in their first 10 years may be more important than previously thought. That includes how they were born (cesarean section versus vaginal delivery), whether they were breastfed, what kind of antibiotics they were exposed to, and what they ate—especially the balance between processed and fiber-rich whole foods.

The gut microbiome, which stabilizes by about age three, is shaped by these early experiences. Strains of E. coli that produce colibactin are part of the normal microbial ecosystem in many people. But under certain conditions—like inflammation, dietary changes, or shifts in microbial competition—these bacteria may become more dominant or more likely to produce the toxin. That could explain why not everyone who carries these bacteria develops cancer-related mutations.

Interestingly, the study also found that the presence of colibactin-related mutations was not always matched by the detection of colibactin-producing bacteria at the time of diagnosis. This supports the idea that the exposure happened much earlier and that the microbiome changed over time. In short, the damage may already be done years before any symptoms appear, making early life a key period for risk.

What This Means for Prevention and Early Action

As research into early-onset colorectal cancer progresses, one thing is clear: the disease doesn’t always wait until later life, and prevention efforts shouldn’t either. While we can’t change early-life exposures retroactively, there are actionable steps individuals and healthcare providers can take now to reduce risk and catch cancer earlier.

- Symptom awareness remains critical: Young adults often delay seeking care for symptoms like blood in the stool, persistent bloating, or unexplained weight loss—assuming they’re too young for serious conditions. This mindset needs to shift. Earlier recognition and follow-up can mean earlier-stage diagnosis and better survival outcomes.

- Screening may need to start sooner for some: Current guidelines recommend screening from age 45 for average-risk adults, but this study suggests a future where genomic or microbiome-based tools could help flag higher-risk individuals even earlier. Detecting DNA damage from colibactin in stool samples, for instance, may become part of personalized screening strategies.

- Lifestyle still matters: Even if some exposures happen early, adult behaviors can influence overall cancer risk. A low-inflammatory, whole-food diet, regular exercise, and limiting alcohol and tobacco use remain important. These factors support overall gut health and may reduce inflammation that allows harmful bacteria to thrive.

Lastly, emerging research is exploring new tools to manage gut microbial balance. Probiotics, dietary interventions, or targeted therapies may one day help reduce exposure to colibactin-producing strains—but for now, prevention still starts with awareness and early clinical engagement.

A Parent’s Guide to Nurturing a Healthy Gut from the Start

The gut microbiome begins forming at birth, and what happens in the first few years of life can set the tone for long-term health—including risk for conditions like colorectal cancer. While the recent findings on colibactin point to very early DNA damage as a potential contributor, the broader lesson is this: early gut health matters. And there’s a lot parents can do to support it—without needing to reach for trendy supplements or carb-heavy foods.

- Start with what’s natural: Breastfeeding plays a key role, feeding good bacteria and supporting immune development. These are decisions influenced by many factors, so perfection isn’t the goal—but informed choices matter when they’re available.

- Be mindful of antibiotics: Antibiotics save lives, but they also wipe out beneficial bacteria. In infants and young kids, overuse—especially for non-serious infections—can disrupt microbiome development. When antibiotics are needed, follow up with gut-supportive foods, not necessarily probiotic pills.

- Feed the microbes—without loading up on sugar: While mainstream advice often pushes grains and fruit juice for fiber, there are keto-aligned ways to support the gut. Think non-starchy vegetables (like zucchini, spinach, and cauliflower), fermented foods (like sauerkraut and unsweetened yogurt), and omega-3-rich fats. These help nourish the microbiome without triggering insulin spikes.

- Avoid ultra-processed foods: What kids eat in their early years—especially packaged snacks high in additives—can shape microbial balance for years to come. Prioritize whole, real food whenever possible. If you’re already eating keto at home, your child is likely benefiting from a low-inflammatory, gut-friendly environment.

Gut health isn’t just about digestion. It affects how we absorb nutrients, regulate inflammation, and possibly, how our DNA responds to bacterial toxins like colibactin. The good news is that every thoughtful choice you make—starting from infancy—helps build a stronger foundation.

Your Gut Remembers More Than You Think

Most of us don’t think about our risk for cancer in our 20s or 30s—but that’s exactly what makes this new research so important. Scientists are beginning to understand that the groundwork for some cancers may be laid much earlier in life, even in childhood, through things like diet, medication use, and the bacteria that live in our gut.

What’s especially striking is that a single toxin, colibactin, produced by certain gut bacteria, may leave behind a kind of scar on our DNA. These mutations can linger for decades before cancer ever develops. And while we can’t rewind and change the past, we can start paying closer attention—to our symptoms, to our gut health, and to the choices we make for ourselves and our families.

If you’re a young adult with persistent digestive symptoms, don’t brush them off. Talk to your doctor. If you’re a parent, know that everyday choices—how your child eats, their exposure to antibiotics, how their gut develops—might matter more than we once realized.

It’s not about fear. It’s about being proactive. Because when it comes to cancer, earlier action and a little awareness can go a long way.

Source:

- Díaz-Gay, M., Santos, W. D., Moody, S., Kazachkova, M., Abbasi, A., Steele, C. D., Vangara, R., Senkin, S., Wang, J., Fitzgerald, S., Bergstrom, E. N., Khandekar, A., Otlu, B., Abedi-Ardekani, B., De Carvalho, A. C., Cattiaux, T., Penha, R. C. C., Gaborieau, V., Chopard, P., . . . Alexandrov, L. B. (2025a). Geographic and age-related variations in mutational processes in colorectal cancer. medRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.13.25322219

Ivy West

Thursday 15th of May 2025

Free image sharing. https://imgsrc.me/