Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurological condition that affects nearly a million people in the United States alone. It disrupts communication between the brain and the rest of the body, leading to symptoms that range from numbness and weakness to difficulty walking or paralysis. Despite decades of research, the exact cause of MS remains unclear. Scientists know that genetics, environmental factors like vitamin D levels, smoking, obesity, and infections such as the Epstein-Barr virus all play roles. Still, no single factor fully explains why the disease develops.

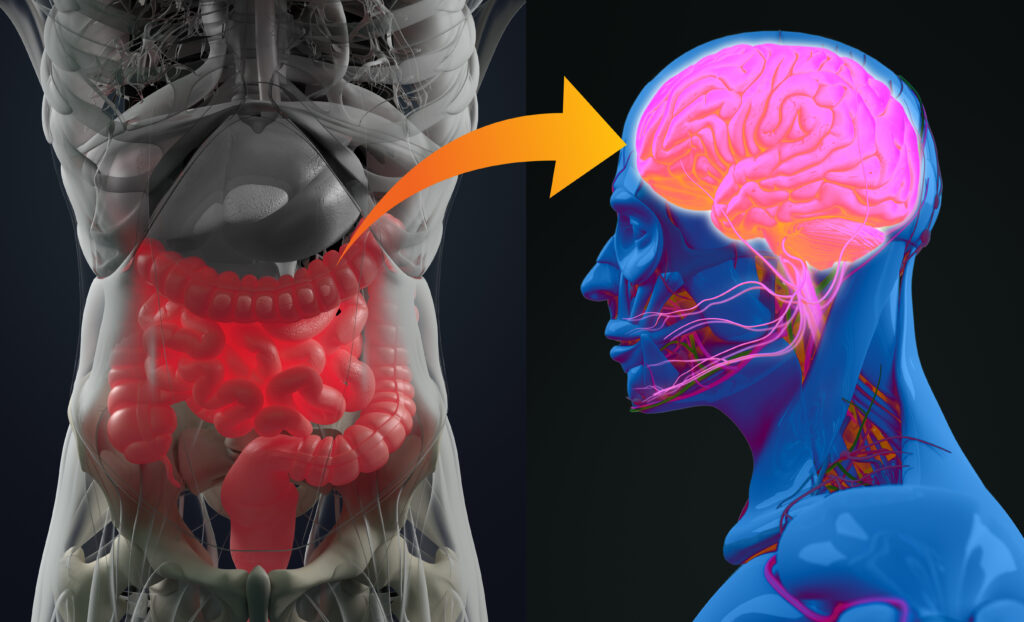

Recently, attention has turned toward the gut microbiome—the vast community of bacteria living in our intestines—as a possible piece of the MS puzzle. New research suggests certain gut bacteria may trigger or worsen the immune system’s attack on the nervous system. This shift in thinking opens up new possibilities for understanding MS and, potentially, for its treatment and prevention.

Identical Twins, Different Outcomes: Studies Reveal Clues

Understanding what causes multiple sclerosis is difficult because both genetics and environmental factors play roles. Identical twins share nearly 100% of their DNA, yet sometimes only one twin develops MS. This unique situation provides a powerful way to study what environmental differences might trigger the disease.

Researchers at the University Hospital of Munich conducted a large study involving over 80 pairs of identical twins where only one sibling had MS. By comparing their gut microbiomes—the communities of bacteria living in the intestines—they aimed to identify specific bacterial species linked to the disease. Because the twins share the same genetic makeup and often similar early life environments, differences in their gut bacteria could point to factors influencing MS development beyond genetics.

The researchers found 51 types of bacteria that varied significantly between affected and healthy twins. This finding suggested that certain gut bacteria might contribute to MS risk or progression. However, identifying differences was just the first step. The critical question remained: do these bacteria actually cause or worsen MS, or are they simply a byproduct of the disease?

To answer this, scientists needed to move beyond observation and test whether these bacteria have a direct role in triggering MS-like symptoms, which led to the next phase of the research involving germ-free mice.

Lab Experiments Confirm That Gut Bacteria Can Worsen MS Symptoms

To determine if the gut bacteria found in MS patients could actually trigger the disease, researchers used a controlled lab experiment involving mice. They took intestinal bacteria from the twins—both those with MS and their healthy siblings—and introduced these microbes into germ-free mice bred to be genetically susceptible to MS-like symptoms.

These mice, raised in sterile conditions without any bacteria, allowed scientists to observe the direct effects of the transferred human gut bacteria without other microbial interference. The results were striking: mice that received bacteria from the MS-affected twins developed MS-like symptoms at a significantly higher rate than those given bacteria from healthy twins.

This approach marked an important shift from merely noting correlations to demonstrating a functional role for gut bacteria in MS development. It showed that specific microbial communities could actively provoke autoimmune responses that damage the nervous system.

Importantly, this model also reflected some key features of MS in humans. Female mice were more likely to develop symptoms, mirroring the higher prevalence of MS in women. The study highlighted that the gut bacteria’s influence extends beyond the intestines, triggering immune cells that travel to the brain and spinal cord to cause inflammation.

How Gut Microbes Fuel Autoimmune Attacks in MS

The study identified two bacterial species—Eisenbergiella tayi and Lachnoclostridium—as likely contributors to MS-like disease. Both belong to the Lachnospiraceae family, which normally includes bacteria with varied effects on the immune system.

Although these bacteria are minor components of the human gut microbiome, they expanded dramatically in mice that developed MS symptoms. This suggests they can gain dominance under certain conditions and influence disease progression.

Researchers believe these bacteria trigger immune responses by activating a type of immune cell called Th17 cells, which are abundant in the small intestine. When activated, these cells produce inflammatory signals that can mistakenly attack the nervous system, damaging the protective myelin sheath around nerve fibers. This process disrupts communication between the brain and body, causing symptoms like weakness, numbness, and loss of coordination.

The study also observed that female mice were more susceptible to this gut-driven autoimmune response, reflecting the real-world pattern where women are diagnosed with MS at higher rates than men. This finding points to an interaction between gut bacteria, immune function, and sex hormones that requires further investigation.

Importantly, not all bacterial expansions triggered disease. Other bacteria that increased in abundance, such as Akkermansia, did not cause MS-like symptoms in mice, highlighting the specificity of the disease-associated microbes.

Gut Microbiome and Autoimmune Disease: What’s the Connection?

Our gut is home to trillions of bacteria and other tiny organisms that help us digest food, produce vitamins, and keep our immune system in check. When everything’s in balance, these microbes help the immune system tell the difference between harmful invaders and our own healthy cells. But when that balance gets off—something called dysbiosis—it can lead to chronic inflammation and even autoimmune diseases.

In those cases, the immune system gets a bit overzealous and starts attacking the body itself. We’ve seen this happen in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes. Now, research suggests something similar might be going on with multiple sclerosis.

Some gut bacteria seem to trigger immune cells in the small intestine—like these pro-inflammatory Th17 cells—that can then travel to the brain and spinal cord. Once there, they attack the protective layer around nerve fibers, which messes with how the brain talks to the rest of the body. That’s what leads to symptoms like muscle weakness and coordination problems in MS.

This connection between the gut, brain, and immune system gives us a fresh way to understand why MS shows up in some people even when their genetics look similar. It also opens the door to new treatments focused on changing the gut bacteria, which is pretty exciting.

The Potential of Gut Microbe Therapy

These findings suggest a potential shift in how MS could be diagnosed and treated. Instead of focusing solely on suppressing the immune system, future approaches might target the gut microbiome to prevent or reduce disease activity.

Therapies that specifically reduce harmful bacteria like Eisenbergiella tayi and Lachnoclostridium or promote beneficial microbes could offer more precise control over autoimmune responses. Options under investigation include targeted probiotics, selective antibiotics, dietary adjustments, and even bacteriophage therapy, which uses viruses to attack specific bacteria.

Such microbial-focused treatments could work alongside existing medications, possibly lowering the need for broad immunosuppression and its associated risks. They may also provide new hope for early intervention before symptoms worsen.

However, these strategies are still experimental. The complex interaction between gut bacteria, the immune system, and individual genetics means that treatments will need to be carefully tailored and tested in clinical trials before becoming widely available.

Everyday Steps to Support a Healthy Gut

While research on gut bacteria and MS is still developing, maintaining a balanced gut microbiome supports overall immune health and may help reduce autoimmune risks. Here are some practical steps anyone can take:

- Eat a varied diet rich in fiber and fermented foods: Foods like vegetables, fruits, yogurt, and kimchi feed beneficial gut bacteria and promote diversity.

- Avoid unnecessary antibiotics: Antibiotics can disrupt gut bacteria, so use them only when prescribed and necessary.

- Manage stress: Chronic stress affects gut health and immune function. Techniques like mindfulness, meditation, or gentle exercise can help.

- Stay physically active: Regular movement supports digestion and immune balance.

- Consult your healthcare provider: Before starting probiotics or supplements, especially if you have an autoimmune condition, get professional advice to ensure safety and appropriateness.

These steps won’t prevent MS on their own, but they contribute to a healthier gut environment, which research suggests plays a role in immune regulation.

The Future of MS Treatment

Multiple sclerosis remains a complex disease influenced by genetics, infections, and environmental factors. The discovery that specific gut bacteria may trigger or worsen MS offers a new perspective, but it’s important to approach this finding with balance.

Gut bacteria are not the sole cause of MS, but part of a larger picture involving how our immune system interacts with the world around us. More research is needed to confirm these results in humans and develop safe, effective microbiome-based therapies.

In the meantime, staying informed about gut health and working closely with healthcare providers can empower those at risk or living with MS to make thoughtful choices. Supporting continued research and spreading accurate information will help move this promising field forward.

If you or someone you know is affected by MS, consider discussing gut health with your medical team. Small steps today may open the door to better management and prevention strategies tomorrow.

Source:

- Yoon, H., Gerdes, L. A., Beigel, F., Sun, Y., Kövilein, J., Wang, J., Kuhlmann, T., Flierl-Hecht, A., Haller, D., Hohlfeld, R., Baranzini, S. E., Wekerle, H., & Peters, A. (2025). Multiple sclerosis and gut microbiota: Lachnospiraceae from the ileum of MS twins trigger MS-like disease in germfree transgenic mice—An unbiased functional study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(18). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2419689122